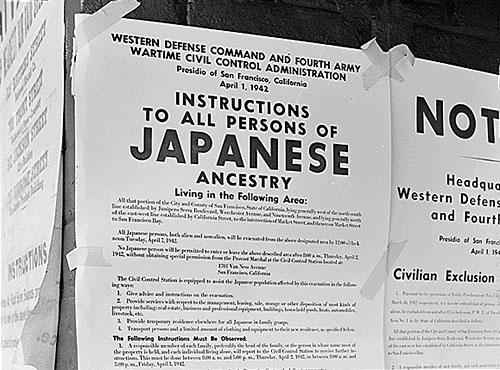

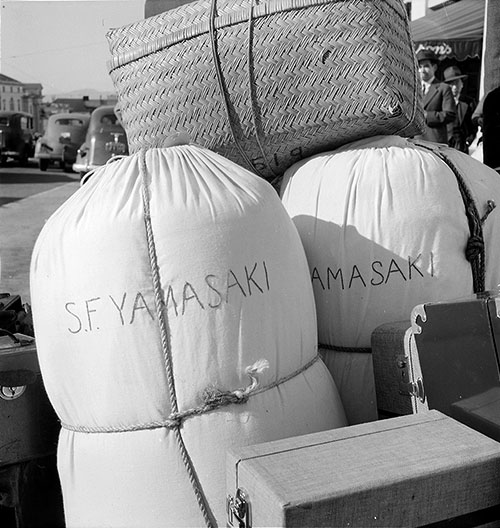

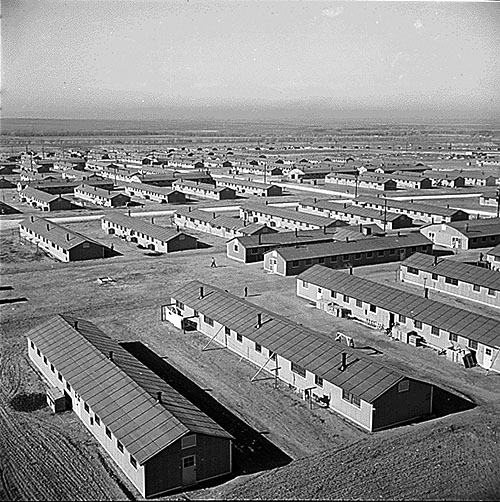

You’re in shock. You can’t believe it. But there it is—instructions posted on the street corner addressed to all people of Japanese ancestry living in California, Oregon and Washington. The United States government is uprooting you from your home and sending you to one of 10 internment camps across the country.

Do you…